Projet de recherche, financement RCDAV 2017–2019

Haute école d’art et de design – Genève

Prison: a Transdisciplinary Workshop Facing a “Lost Cause”

Prisons around the world are sites of all human inequalities. Yet detention conditions, however frightening, do not make much of an impression on society as a whole. Design and visual arts students reflect on what means to use to communicate about a cause that seems well and truly lost in advance.

+

Transdisciplinary Research Workshop, Masters Program in Design and Marketing (Design) & Masters Work Project (Visual Arts), October 29–November 2, 2018

Ruedi Baur, Caroline Bernard, Damien Guichard, Heder Neves

Prisons are violent asymmetrical systems that are not well known to citizens, but which are generally thought to be indispensable. This workshop proposes to simultaneously infiltrate urban spaces and social networks while attempting to initiate socially committed buzz. This workshop was created in collaboration with Prison Insider, whose international mission is to take stock of the situation as concerns prisons and prisoners throughout the world.

Virality is not the prerogative of one discipline. Consequently, collaboration between designers and artists enables us to shed the conditioned reflexes of our occupations in favor of the benefits of a more open and successful approach. Forms of communication to be invented are always in an intermediate space. The practices of interior design or graphic design are thus replayed through the prism of visual art and vice versa. Over the course of our two years of work, it was necessary for us to operate within the bounds of pedagogy. The use of social networks is generational for us, therefore students connect to them in a specific way. For example, Facebook is not their platform of predilection; they have more presence on Instagram and other messaging tools. Working with them was a fortunate opportunity for the research team since, as digital natives, the students had been acquiring their Internet skills since childhood. In addition, since they were highly connected in their private lives, the students did not necessarily visualize their jobs through them. Such pedagogical experiments enabled them to gain an understanding of how to integrate issues of communication within social networks.

Ruedi Baur and Vera Baur: Montluc Prison

Ruedi Baur, a professor at HEAD– Genève and a politically committed graphic artist, was often confronted by the harshness of the theme of prison. His project at the Montluc Prison is an example of a raising of public awareness to initiate an open debate without judgment.

+

For this workshop, our research team was invited by Ruedi Baur, who, as part of his teaching at HEAD–Genève, proposed that students conceive a social design. As someone pretty politically committed in his personal life, he was already collaborating regularly with Prison Insider. His project on the Montluc Prison, realized with sociologist Vera Baur, is an example of the use of design dedicated to the raising of social awareness to address societal issues and encourage the public to ask question.

The military prison of Montluc was opened in 1921 and was in use by the Vichy regime from 1940 to 1943. It was then requisitioned by the Nazi occupiers from January 1943 to the end of August, 1944. During that period, the prison became a central point for executions and a hub for deportations in the region of Lyon. Ten thousand men, women, and children were imprisoned there during the Nazi occupation, notably the children of Izieu, Jean Moulin and Marc Bloch. The national memorial of the Montluc Prison, which pays tribute to the victims of the Second World War, was inaugurated in 2010.

The association Les Ouvriers Qualifiés and the National Memorial of Montluc Prison invited Ruedi and Vera Baur, of the association Civic City, for an artist’s residency. They put together and wrote out 1,500 questions concerning the history and future of the site of the Montluc Prison. The questions were set out in calligraphy by Afrouz Razavi and Eddy Terki on small pieces of wood which were set out throughout the prison space during the European National Heritage Days (Journées Européennes du Patrimoine). These questionings revisit the layers of memory held within this military and civic prison. Consequently, these questions confront the public but the answers remain latent within the immensity of this memorial space. Each historical aspect is not described with a sententious affirmation but rather through the prism of a questioning, which reopens the possibilities of the past, as if it were still possible to change it: “Were conscientious objectors also imprisoned here?”; “Who would have been selected to shoot them?”; “What arms were used?” These wooden, thought-provoking plaques work as phylacteries of a sort that accompany the visitor as they wander through the space.

Within the scope of our research, this installation attests without meaning to the same dynamics we have found on social networks: the power of open questions. In fact, if a message has to present conversational qualities, the simplest way to go about it is to ask a question. On social networks, the interrogative form is almost certainly the simplest form of initiating a dialogue online. During our collaboration with groups from the Gilet Jaune movement, one question among others, set out on a yellow Post-It™, ended up as a central element of public social dialogue.

Prison: a Distasteful Theme

Considered a necessity, a prison is, in and of itself, not a theme particularly predisposed to virality. It is difficult to raise this subject of discussion with the same perspective as a human interest news item, which is more likely to touch people sensibilities.

+

At the time of the workshop, in the fall of 2018, the theme of prisons was not the beneficiary of a unifying hashtag such as #MeToo, which was in the process of upending stereotypes regarding violence against women and galvanizing feminist consciousness. Prison is a difficult theme, one that is little inclined to generate a social buzz that is unanimous and subject to consensus. We encountered the same difficulties as we had with our project on the Rom community: a subject ahead of its time both politically and socially is laden with current prejudices. Civil society generally believes that, for the common good, prison constitutes a necessary evil, the only bastion against rampant criminality. Denouncing the prisoners’ disastrous conditions of detention or the denial of their rights is not an easy task since everyone believes that they get what they deserve.

While they proved quite interesting, the experiments conducted as part of this workshop did not have the impact of the Café Cunni project. The assembled teams were certainly smaller, but, despite their courageous efforts, one must concede that such a debate, outside of any galvanizing current event, is simply more difficult to perpetrate in the flow of social networks. We encountered this in our experiment Buzz for the Sake of Buzz. The video of the wandering patient triggered empathy for the image, as did the photo of the child Aylan. As a result, the web surfer mobilizes to relay the information. One must not confuse this with the sensationalistic mechanics of the tabloid press. Cybernauts share only what means something to them, and, amidst the flow of information, their attention is only fixed on things that are most recognizable to them.

How does one generate awareness among users of social networks when no form of personal projection is really possible? In the case of the #MeToo movement, half of humanity is female, so this generates immense volumes of potential shares. As for prison, even the family members of prisoners are reserved about defending their imprisoned nearest and dearest, since they do not wish to air their dirty laundry.

Fortunately, institutions such as Prison Insider exist, but a number of individuals who accept being standard-bearers for such an issue, the only guarantee of a minimal number of messages being distributed, does not seem to exist as such. The two experiments that we retained from this workshop actually presaged the possibility of bringing communities together and having them emerge through innovative approaches.

Prisoners as Designers: Designers in Dialogue

The concept behind the Prisoners Are Designers Project is that prisoners interact with the community of designers through the savoir-faire they have acquired over the course of their detention.

+

The Prisoners Are Designers Project is based upon an interest in the skills acquired by prisoners. Over the course of their detention, they often clandestinely conceived objects with very little means.

In order to improve the conditions of their detention, prisoners had no other choice but to invent new ways of making things. The objects created also attest to the precarity of life in prison. By following their process, students sought to understand the inherent processes of this “design in detention” in order to imagine new methodologies of creation.

Eventually, they decided to create ateliers to include former detainees, people working in prisons and designers in order to exchange on the topic of Design in Detention Conditions. Consequently, former detainees, invited as experts, shared their little-known methods of creation and transmitted their skills. This exchange of expertise enabled them to open up discussion on their conditions of incarceration.

While it seems impossible to unite the public around prison issues, this hypothesis has the merit of conceiving the creation of a targeted group, that of designers. Designers who pay attention to prisoners, perceiving them through the prism of an expertise in design that was, until now, not associated with them. The designers were not positioned as people who knew better, but rather as a group that had something to learn. Thus, this project, which is founded upon a horizontal sharing of knowledge, opens up a line of approach, creating a dialogue between the design community and prisoners, who can also use this as an avenue for denouncing the conditions of their detention.

#9m2: Occupying a Hashtag

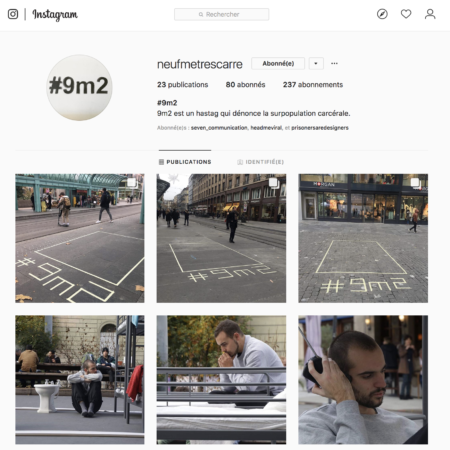

The hashtag #9m2 is generally used to refer to the size of an apartment or dorm room. The goal of this experiment was to “occupy” it, appropriating it in order to lend visibility to messages denouncing detention conditions throughout the world.

+

Prisons the world over are generally deplorable places that range from being unhealthy to utterly horrific. Detainees are packed into minuscule cells with very limited access to basic necessities. While international norms dictate that a maximum of three detainees occupy a nine square meter cell, depending on the country, one can find four to nine inmates in a space as large as nine square meters. Privacy is not an option.

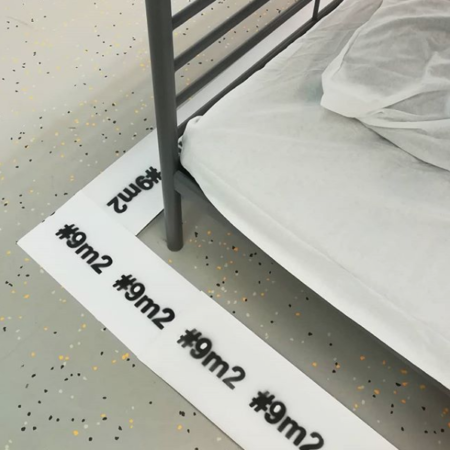

In order to expose this situation, the proposal consists of setting out marks on the ground in various places, taking photos of them and publishing them on social networks. With a simple roll of duct tape, people would outline the limits of a cell and use the tape to inscribe “#9m2” within it. An ephemeral marking, the action can easily be repeated everywhere. Once photographed, the published images can be tagged with the name of the city, for example #geneve, as well as the unifying hashtag #9m2.

Here, the aim was to occupy the #9m2 hashtag. Unlike the #MeToo hashtag, #9m2 already was in existence and was generally used in reference to the size of lodgings in cities like Paris. Nine square meters is also the standard size of a student dorm in many countries. Here the objective was to occupy the area, and appropriate this hashtag precisely in order to juxtapose these images with existing publications. This enables them to become part of a preexisting flow and finally become visible.

This project was easy to implement and will continue. Here, the design consists of a series of simple instructions, an easy formula that only requires a roll of tape and a hashtag to create it. The idea is to manage to acquire images from all over the world, created by people already aware of the issues and who have accepted to increase the impact of the operation, say by taking new photos when they take a trip. The more images, the greater the visibility.